Snapshots of Dementia: For Such a Time as This

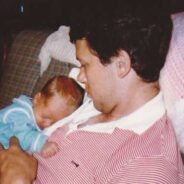

by Andrew Pieper Tom with baby Andrew, 1991 “OK, love you too, bye,” I said—my standard farewell on my weekly video calls with my mom and dad. Yet the call had felt anything but standard to me. The outside observer probably wouldn’t have noticed, yet there were subtle signs that left me with a sinking feeling. We had talked about many standard topics and events: church, work, happenings around town, but today I had to refresh my dad’s memory on multiple subjects, things we had talked about only a few days ago. Dad “knew” everything we talked about in great detail, yet he had no idea about any of them. This conversation lingered in my mind over the next week. I kept thinking of my dad, sitting there in his recliner, happy and content. Yet to me, who knew him as the witty, loud man who would often throw the childhood me up in the air to questionable heights of safety before gracefully catching me, he had become someone else entirely. Over the next several days, after a lot of thinking and praying about what I should do, I decided the best thing would be to pack my bags, leave Texas, where I had been living for a few months, and go to be with my parents for a while. Being the only boy among four sisters, my dad and I have always had a special relationship, but it’s changing now—and will continue to do so. Neither of my parents was ever “handyman inclined,” so whenever I came for visits, I assisted them with such tasks as replacing lights, pressure washing, and landscaping. By living with them, I could help alleviate some of the day-to-day tasks from my mom, who currently is wearing multiple hats, working full time while taking care of my dad, the house, and the yard. How long would this last? For the next six months? Six years? I have no clue on the timeline, but one thing that I strive to keep at the forefront of my thoughts is to have a heartbeat of obedience to God’s calling. I don’t want to have any preconceived “noes” in my mind for where God might call me or what He might call me to do. Just like that, I began the process of closing my storage unit and packing things up. Within two weeks I was ready to go; my van and trailer and I made the drive to South Carolina. It is only my second week since relocating here, and already God has given me multiple signs that this is the right move for this season of my life. First, my mom got sick with COVID this past week, so instead of primarily being concerned with the health and well-being of one parent, it has now been two. Thankfully, both my dad and I have tested negative, and while my mom’s energy has been wiped, she seems to be recovering now since taking some medication. The other day I was working on my motorcycle in the driveway, and my dad came out of the house, leaning on his walker. I looked up from my bike to see what he needed. “I was just wondering where you were,” he said, then turned and made his way...

read moreSnapshots of Dementia: That’s Just the Way It Is?

(Terri Cnuddle from Pixabay) It seemed easy enough. Some friends from our time in Charleston were visiting our small town and wanted to stop by for a brief visit. Trying to keep things simple, they planned to eat lunch before they came; we’d use our time together to talk and catch up. This visit was simple—much too simple when it came to Tom. For the most part, all he did was sit and listen to our conversation. Years ago, the woman and I had been part of the same homeschool group, and we eagerly discussed everything from where our children were living to the health of our mothers, now both widowed and in their 90s. My friend’s husband contributed here and there, but mine was almost completely silent. The only time he spoke was when I encouraged his agreement about one point or another as I continued my non-stop discussion. “You notice he’s hardly saying anything,” I mentioned to our friends when Tom stepped out of the room. They nodded. Before long, Tom was back, and we finished our visit much the same as we started it—the three of us doing most of the talking and Tom an almost-silent observer. Only after they left did I realize what I’d done—or what I hadn’t. In my eagerness to visit with my friends, I’d left Tom hanging in the breeze of our conversation. I’d acted as though I didn’t know how to interact with someone who is living with dementia. And worse, I’d behaved as though it didn’t matter. “That’s just the way it is,” I’d implied. Yes, that’s just the way it is—if I’m selfish. That’s just the way it is—if I’m not intentional. That’s just the way it is—if I don’t listen to the Holy Spirit about how to bless my husband. That’s just the way it is—if we don’t treat people LWD with the respect they deserve. Only a few days later, I invited another friend over for dinner. His wife was out of the country, and I thought he might enjoy some company and home-cooked food. As I prepared the meal, I realized that—both because of his love for Tom and his own prior caregiving experience—our friend would make a great co-laborer. Together, we could give Tom a different experience than I had with our previous guests, but it would require intentionality on both our parts. When our friend rang the doorbell, I made sure I answered. This is often what happens anyway because Tom tends to stay in his recliner, most often playing on his iPad. Our friend and I had a quick porch chat before entering the house. I told him about the recent visit and how Tom had largely remained silent. “This time, I’m going to try not to say too much,” I told him. “And I need you to think of things to ask him about. I’ll jump in sometimes, but I’m going to try to let him do most of the talking.” “I’m looking forward to it!” our friend said. We had a plan. Now, it was time to apply it. Although Tom loves and appreciates this friend, he barely looked up as I brought our friend into the family room. “I need to go finish up supper,” I told...

read moreSnapshots of Dementia: I Get That a Lot (and Why I Shouldn’t)

(TC Perch on Pixabay) You’re so patient.” “I don’t know how you do it.” “You’re an example for others.” I get that a lot. And to be honest, I shouldn’t. I understand why. In sharing snapshots of our life while living with dementia, I do my best to be as transparent as I can. But I know there are things I miss. And I also understand that my perspective is not the only one. When I teach on writing memoir, I encourage people to tell their own story, even if it’s not the way someone else remembers it. That’s what I seek to do here. So even though my story of LWD is not the same as someone else’s, it is my story—and thus our story, the best I can tell it, for both Tom and me. But I want to apologize for the times—past, present, and future—I may make myself sound better than I am. Because here’s the real truth: I am so not. Not patient. Not kind. Not good. Not any kind of example for anyone. Left to my own devices, I am just the opposite: impatient, prideful, selfish, self-centered, easily irritated, controlling, and so much more. In fact, I’m probably less likely than most people to be a good caregiver for someone who is LWD. But here’s the thing: The truths we celebrate this Easter weekend matter. And they changed my life. I grew up with two wonderful parents who faithfully took me to church. The sermons I heard and lessons I learned shaped my standards and values. But until my junior year in college, they reached no further than my intellect. If you had asked me back then, I could have told you that yes, Jesus died on the cross. I would have said that yes, God raised Him from the dead. And I would have also said that I might go to heaven someday, that I tried to do good things to gain that privilege. You see, I grew up trying to do lots of “good things” so I would avoid getting into trouble. That’s not a bad way to start out, but it’s not a great place to stay. And it didn’t give me a great picture of the God I know today. You see, that God created me to love and serve Him, to honor Him with my life. He knew I could never do that on my own. Remember? Left to my own devices, I am impatient, prideful, selfish, self-centered, easily irritated, controlling, and so much more. Until my college years, I didn’t understand that I could never be good enough for God; I needed Him to be good for me. His death on the cross was not a symbolic act but a personal one. He took the punishment I deserved. He died the death I earned. When I placed my faith in Christ, I not only received the promise that I will live with Him in heaven someday, but so much more: the unmerited ability to live a life I could never live without Him. The undeserved power to do that which I could never do on my own. So when someone tells me “You’re amazing,” or “I could never do what you do,” I want to tell them the truth:...

read moreSnapshots of Dementia: If You See Something, Say Something

(Israel Palacio on Unsplash) He’s quirky.” Anyone who’s known Tom through the years will agree that I wasn’t wrong when I described him this way to a group not long after we had come to the final church he served as minister of music. He’s a musician; I’m a writer—we pretty much understood that quirkiness was part of the package when we married each other. But now, I wonder just where his quirkiness stopped and the dementia behaviors began. And I don’t suppose I’ll ever know. I missed many of the early signs that Tom was living with dementia—partly because his neurologist and others kept telling me he was fine. But because I didn’t know about the behavioral issues dementia can cause, I am writing about them now so perhaps someone else won’t have to wait as long for a diagnosis as we did. Not everyone LWD exhibits these same behaviors, and not everyone LWD has as many behavioral issues as those with a variant that affects the frontal lobe. But in addition to those I noted last week, here are some more of the atypical behaviors we saw in Tom even before he received his dementia diagnosis: — IMPULSIVE/RECKLESS ACTIONS: I have written about how he was blackmailed via social media and later gave away thousands of dollars to online scammers. Since he was always frugal, this was out of character financially as well as morally. I am still appalled at the way scammers prey on the vulnerable, but I wish I had recognized just how vulnerable he was much sooner. — LACK OF MOTIVATION: I also wrote not long ago about how Tom stopped paying attention to lawn care. This same lack of motivation, in large measure, resulted in him no longer playing his trumpet (formerly a top priority for him). After he hurt his lip in a challenging concert in 2016, he received a detailed plan to help him heal and rebuild his muscle strength, but he never followed through. He still tells people he’s a professional musician; the sad truth is that he hasn’t practiced consistently since he hurt his lip nearly seven years ago, more than three years before his diagnosis. — ODD PERSONAL HABITS: One day, I found him laying a towel down over the bathmat as he prepared to take a shower. When I asked about it, he said he “had never liked to get the bathmat wet.” It took a while for me to realize this was a dementia behavior, not a longtime preference that I had somehow missed. I remember watching the final funeral he officiated nearly five years ago and noticing how he constantly licked his lips as he spoke. Today, I see (and hear) that behavior whenever he’s not focused on something else, such as when we ride in the car. — INABILITY TO PLAN AND ORGANIZE: I was heartbroken when Tom lost his job as a music minister, but when I think back, I’m amazed he kept it as long as he did. I am sure one reason he could was the wonderful volunteer who kept him organized and on track, but even with her help, his planning became more and more erratic. It takes a lot of organizational skill to set up a worship...

read moreSnapshots of Dementia: It’s Broken (or not)

(Andres Urena on Unsplash) Tom hobbled into the kitchen the other day, a man on a mission. “What’s wrong, baby?” “My Fitbit is broken,” came his gloomy response. “What seems to be the problem?” “It won’t show me the time anymore. It’s broken.” Tom can’t walk for exercise anymore, but he retains his obsession with his Fitbit. He can’t charge it on his own anymore either, but he wants to make sure it’s always ready for use. And when he accidentally switched it over to timer rather than clock mode, he felt sure it was broken. You and I wouldn’t come to that conclusion. But you and I, for the most part, are not people living with dementia. “Here, let me see it,” I said, reaching for the device. Of course, it only took a few taps and swipes for me to return it to clock mode. “Here you go! I got it working again,” I said as I gave it back. It makes more sense to go with his reality than try to explain the details. He took the Fitbit, turned, and walked back to his recliner, his dismay forgotten. Given Tom’s obsession, you’d think he would have been happy and grateful. But although he still expresses happiness and gratitude at times, he does not typically connect those to events such as this one. And in the short time before I returned the device to him, he may have forgotten about his “it’s broken” conclusion. In the days when I didn’t realize Tom was LWD, happenings and conversations like this confused and upset me. Why was he acting this way? The “personality changes” mentioned in lists of dementia signs and symptoms often look different with different people. I’ve heard and read many stories from others whose loved ones are LWD. Since I didn’t realize that some types of dementia initially (and most types eventually) have a behavioral connection, I thought some of Tom’s odd behaviors were just that—odd behaviors, mistakes, or misunderstandings. Looking back (yes, we know what they say about hindsight) I realize that some or all were symptoms of the evil lurking inside his brain. Here are a few more of the changes he exhibited some time before he had a dementia diagnosis: — PESSIMISM: Always an upbeat person, he became a negative one. In the same way the Fitbit was “broken,” the banking website was “messed up,” and his discipline of our “terrible” dog became unduly harsh. For someone whose world is becoming more and more challenging, it’s easy, even natural, to be negative. — APATHY: Tom had less and less interest in family birthdays, anniversaries, even special events such as a couple’s baby shower for our daughter and son-in-love. This was not because he didn’t care, but because he couldn’t. Before we knew he was LWD, this behavior hurt. And when we think about who he was compared to who he is now, at times, it still does. — INAPPROPRIATE ATTENTION TO WOMEN: Tom would ignore me but flirt outright with women in service roles, such as at the grocery checkout. I never heard him say anything sexual, but the fact that he largely ignored me and paid attention to other women bothered me, and I addressed it in our marriage counseling to no avail. He still...

read more